Welcome to March, Reader. I am that much closer to finishing my degree!

In case you missed it rebounding through the news that loves to cover the Church in crisis, my denomination is a bit on fire at the moment. The United Methodist Church held a conference this past week to talk to itself at the highest level of representation about what we believe in regards to sexuality, and what we’re going to do if we disagree about that. I went, and I’m glad that I did because I have so many stories of community built on Ghiradelli squares and snarky commentary, stories of support and of sorrow, stories of parsing through the seemingly labyrinthine legislation and of trying to find the Spirit in the machinations of factions quietly politicking around each other in the name of the Holy. It was a beautiful, ugly, extraordinarily human few days.

In case you missed it rebounding through the news that loves to cover the Church in crisis, my denomination is a bit on fire at the moment. The United Methodist Church held a conference this past week to talk to itself at the highest level of representation about what we believe in regards to sexuality, and what we’re going to do if we disagree about that. I went, and I’m glad that I did because I have so many stories of community built on Ghiradelli squares and snarky commentary, stories of support and of sorrow, stories of parsing through the seemingly labyrinthine legislation and of trying to find the Spirit in the machinations of factions quietly politicking around each other in the name of the Holy. It was a beautiful, ugly, extraordinarily human few days.

The end result is that the more conservative faction within the UMC (made up mainly of delegates from a corner of the American South, parts of Africa, and pieces of Eurasia like Russia and Kazakhstan) pushed through some legislation that doubles down on the idea that “homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching.” It also insists that any pastor who officiates or otherwise supports homosexual relationships should be punished by the Church, up to and including being defrocked. And anyone falling under the term “homosexual” (which was broadened to catch other folks in the LGBTQ [Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning] community) cannot be ordained as long as they hold to that identity.

This breaks my heart, Reader, for many reasons. Most personally, it breaks my heart because it catches me. You see, I am bisexual. But I am also United Methodist, Christian, a lefty, a poet, a white woman, a Trekkie, a cat person, an amateur calligrapher, a friend, a decent baker, a preacher, a chaplain, a daughter of God. I have absolutely no difficulty holding all of these identities together at any given time. I do not find them to be incompatible with each other at all, and given all of these pieces of me I find that I am still called to ministry. If you’ve been around this blog for a minute, Reader, you can see that I fought that call for as long as I could; I didn’t make up the idea that I should be ordained, that I in all of these identities have been asked to be part of God’s Church in this way. So for my denomination’s conference to tell me that people like me are abominations, that we cannot be called to ministry if we continue in our sinful ways—that simply doesn’t match my experience, and it baffles me.

The reasons so many folks focus on anything other than heterosexuality as the focus of sexual sin doesn’t baffle me. During the conference, several amendments were offered to similarly strengthen the penalties around acceptance and ordination of those who are divorced, or those in polygamous relationships, or those who are not celibate outside of marriage, or those who are adulterous—all of which have plenty of Scriptural grounding as sexual sins. None of them passed, because this isn’t actually about sexual purity. I’m not here to have the argument about the verses or the interpretation or whether homosexuality is a sin; if you’re curious about my take on that, ask me, but I am not going to sermonize about that here. I am going to point out that this is a narrow definition of sexual purity and leave at that.

I’m also going to point out the fear of losing relevance. At this conference, I listened to delegate after delegate speak from the Congo, from West Africa, from Central Russia, all mentioning that in their home countries they were losing ground to Islam. If we give up on this issue, the delegates threatened, we as a Church would no longer be acceptable to those looking for a worship home and people would go be Muslim instead.

This line of thinking makes me curious, because either we believe that Jesus is the Lord of all or we don’t. If accepting gay folk can dilute the power of Christ’s sacrifice and resurrection, we need to seriously rethink the idea that God’s word “shall not return to Me empty. Instead, it does what I want, and accomplishes what I intend” (Isaiah 55:11, CEB). Do we believe that we carry the message that will transform the world or don’t we? I get that that doesn’t answer the question of sin around sexuality, but that’s because it tosses it away. God is an unstoppable force, and if we truly believe in the power of this good news that we are loved enough for the Creator of the universe to take on human form, eat with friends, heal the sick, speak to the outcast, be betrayed, die gruesomely, and defeat death through the resurrection triumphant, then nothing we do can derail that news. God doesn’t need us for shit, which is one of the reasons that I love Christianity so much. God doesn’t need us, but God wants us, God invites us, God calls every single one of us to this grand design even though every single one of us has sins for days. If we’re going to bend ourselves around this one thing called sinful (through some weird, twisty readings of Scripture) in order to hold Islam at bay, we are both thinking that we are the guardians of God and we are not trusting that God is already upholding us through the other things we are doing that can be called sinful.

In moving forward, the UMC has lots of challenges. There are ethics violations, constitutional questions, and hosts of problems with the legislation that was just rammed through the process. We as a denomination need your prayer while we untangle this mess, especially since it’s entirely possible that none of what just happened will stick after all of the inquiries and lawsuits. We of The United Methodist Church are not united but divided, and that sucks all around. I do not like fighting with my family, even if a goodly portion of them seem to love fighting with me. So please, pray for us as we discern how to proceed. For my part, I will keep working within this denomination that I love, in this ministry to which I am called, for this God Who knows me inside and out and says a willing heart is what is needed.

“I know that you can do all things;

no purpose of yours can be thwarted.

You asked, ‘Who is this that obscures my plans without knowledge?’

Surely I spoke of things I did not understand,

things too wonderful for me to know.” (Job 42:2-3, NIV)

For starters, I finished my degree, at long last. I now hold a Master of Divinity, which is laughable in the idea that one could ever master divinity. I have moved back to the Land of Pilgrims, reintegrated to my community there, and live in a real people house where I finally have all of my belongings not only in the same state but the same structure. I got rid of 11 boxes worth of stuff that I had picked up either for the life I thought I would have or the life other people were buying for me; it was a bittersweet process, that unpacking. I am currently working as a hospital chaplain, a job at which I am quite good and which flattens me a little more every day with its quiet onslaught of death in all forms. I am working on my ordination papers in this beloved dumpster fire called The United Methodist Church because, against all odds, I still very much want to be a Methodist pastor. And I will be joining a pastoral staff in January, taking all these lessons to a place where I will learn so many more.

For starters, I finished my degree, at long last. I now hold a Master of Divinity, which is laughable in the idea that one could ever master divinity. I have moved back to the Land of Pilgrims, reintegrated to my community there, and live in a real people house where I finally have all of my belongings not only in the same state but the same structure. I got rid of 11 boxes worth of stuff that I had picked up either for the life I thought I would have or the life other people were buying for me; it was a bittersweet process, that unpacking. I am currently working as a hospital chaplain, a job at which I am quite good and which flattens me a little more every day with its quiet onslaught of death in all forms. I am working on my ordination papers in this beloved dumpster fire called The United Methodist Church because, against all odds, I still very much want to be a Methodist pastor. And I will be joining a pastoral staff in January, taking all these lessons to a place where I will learn so many more. In case you missed it rebounding through the news that loves to cover the Church in crisis, my denomination is a bit on fire at the moment. The United Methodist Church held a conference this past week to talk to itself at the highest level of representation about what we believe in regards to sexuality, and what we’re going to do if we disagree about that. I went, and I’m glad that I did because I have so many stories of community built on Ghiradelli squares and snarky commentary, stories of support and of sorrow, stories of parsing through the seemingly labyrinthine legislation and of trying to find the Spirit in the machinations of factions quietly politicking around each other in the name of the Holy. It was a beautiful, ugly, extraordinarily human few days.

In case you missed it rebounding through the news that loves to cover the Church in crisis, my denomination is a bit on fire at the moment. The United Methodist Church held a conference this past week to talk to itself at the highest level of representation about what we believe in regards to sexuality, and what we’re going to do if we disagree about that. I went, and I’m glad that I did because I have so many stories of community built on Ghiradelli squares and snarky commentary, stories of support and of sorrow, stories of parsing through the seemingly labyrinthine legislation and of trying to find the Spirit in the machinations of factions quietly politicking around each other in the name of the Holy. It was a beautiful, ugly, extraordinarily human few days. This time I was determined to learn even though it was daunting and nerve-wracking. My friend and I went out and spent several hours with me lurching around a stadium parking lot, and then I practiced going in circles in my church lot the next day, and the next. A month later, I can say that I can indeed drive a stick—can even parallel park it, if I absolutely must. I’m set to go for the zombie apocalypse as well as every punk who tells me that no girl/millennial/urbanite can drive manual.

This time I was determined to learn even though it was daunting and nerve-wracking. My friend and I went out and spent several hours with me lurching around a stadium parking lot, and then I practiced going in circles in my church lot the next day, and the next. A month later, I can say that I can indeed drive a stick—can even parallel park it, if I absolutely must. I’m set to go for the zombie apocalypse as well as every punk who tells me that no girl/millennial/urbanite can drive manual. Christianity is a light-saturated faith system: God shows up a lot in fire, Jesus is named the Light of the world that is never overcome by darkness, the first moment of creations is to declare that there shall be light. Christmas hangs out right next to this day of hours and hours of darkness exactly because this is when we need light most—this is our version of the prehistoric hope in the fires that burn till dawn, the prayer for the rising sun, we Christians who look to the star shining over Bethlehem.

Christianity is a light-saturated faith system: God shows up a lot in fire, Jesus is named the Light of the world that is never overcome by darkness, the first moment of creations is to declare that there shall be light. Christmas hangs out right next to this day of hours and hours of darkness exactly because this is when we need light most—this is our version of the prehistoric hope in the fires that burn till dawn, the prayer for the rising sun, we Christians who look to the star shining over Bethlehem. We often remind ourselves, as the Church, that the Church is the people rather than the buildings, and that’s good. We should be careful not to get too attached to the structures such that we spend all of our time maintaining them instead of maintaining the communities around them. God didn’t live among us to teach us how to repaint a narthex or replace a boiler; God lived among us to show us how to grieve with the lonely and rejoice with the healing. The people are the Church. But I think that sometimes we fail to see that we humans get attached to stuff whether we’re supposed to or not; we are incarnate creatures seeking safety and belonging, and even those of us with oodles of wanderlust want a place that offers that to us when we are too weary to keep going. We are all, in our own ways, looking for home.

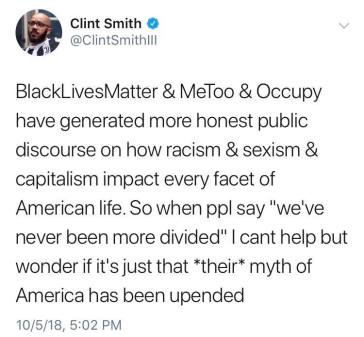

We often remind ourselves, as the Church, that the Church is the people rather than the buildings, and that’s good. We should be careful not to get too attached to the structures such that we spend all of our time maintaining them instead of maintaining the communities around them. God didn’t live among us to teach us how to repaint a narthex or replace a boiler; God lived among us to show us how to grieve with the lonely and rejoice with the healing. The people are the Church. But I think that sometimes we fail to see that we humans get attached to stuff whether we’re supposed to or not; we are incarnate creatures seeking safety and belonging, and even those of us with oodles of wanderlust want a place that offers that to us when we are too weary to keep going. We are all, in our own ways, looking for home. The thing is, that day isn’t today. And it won’t be tomorrow, when I face my congregants and their pain. It won’t be the next day, when I have to talk to people who call this travesty a triumph because it paves the way for things they find more important, pouring tar over the bodies of those in their way. I don’t know when God’s justice will come rolling like a cleansing river. I don’t know when God’s justice will wipe away the tears of those weeping from the wounds of being unheard, of being mocked, of being forced, or forgotten, or used, or broken, or erased. I don’t know when God’s justice will remake this fallen world. But it will. I cannot bear the idea that this world is left to our own devices, we stupid and selfish humans who cannot see the God-light in each other even when it shines like a fucking supernova because we are so damn scared that more of you means less of me when, actually, the infinite compassion of God holds open the edges of the universe itself to make room for the entirety of who God sees we could be.

The thing is, that day isn’t today. And it won’t be tomorrow, when I face my congregants and their pain. It won’t be the next day, when I have to talk to people who call this travesty a triumph because it paves the way for things they find more important, pouring tar over the bodies of those in their way. I don’t know when God’s justice will come rolling like a cleansing river. I don’t know when God’s justice will wipe away the tears of those weeping from the wounds of being unheard, of being mocked, of being forced, or forgotten, or used, or broken, or erased. I don’t know when God’s justice will remake this fallen world. But it will. I cannot bear the idea that this world is left to our own devices, we stupid and selfish humans who cannot see the God-light in each other even when it shines like a fucking supernova because we are so damn scared that more of you means less of me when, actually, the infinite compassion of God holds open the edges of the universe itself to make room for the entirety of who God sees we could be. And will remain dead, and in my estimation will die a hundred thousand more times over the coming years when I reach moments where we usually did something together and he isn’t there, or when I think to text him something funny and remember he won’t answer, or when I want to invite him to things and know he can’t come. Mr. Honest suggested I think of moments like this as ways to say hello to the memory and the spirit of my friend, to invite him in. Mr. Honest is far more compassionate and optimistic than I am.

And will remain dead, and in my estimation will die a hundred thousand more times over the coming years when I reach moments where we usually did something together and he isn’t there, or when I think to text him something funny and remember he won’t answer, or when I want to invite him to things and know he can’t come. Mr. Honest suggested I think of moments like this as ways to say hello to the memory and the spirit of my friend, to invite him in. Mr. Honest is far more compassionate and optimistic than I am. In both the Midwest and the South I often see bumper stickers proclaiming “freedom isn’t free,” which is a sentiment with which I agree in principle if not in application. The concept of freedom, of being able to choose one’s own path, requires payment—whether that payment comes in terms of labor and time on the part of those who came before to guide a system into freedom, or in terms of lives laid down to protect human rights, or in terms of actual money and services paid to unhinge the injustices that perpetuate various kinds of slavery depends on the context in which we discuss freedom. But there is always a cost of some format, and grace is like that. Grace comes at cost, not in a substitutionary atonement kind of way where a vindictive god had to kill his son because we’re all evil but in a kind of way that acknowledges we killed a Man because He rocked our world too far and God took that death and made it redemptive, made it holy, makes us holy a little piece at a time when we realize that God extends grace and then asks for everything that we have ever been and ever will be in return.

In both the Midwest and the South I often see bumper stickers proclaiming “freedom isn’t free,” which is a sentiment with which I agree in principle if not in application. The concept of freedom, of being able to choose one’s own path, requires payment—whether that payment comes in terms of labor and time on the part of those who came before to guide a system into freedom, or in terms of lives laid down to protect human rights, or in terms of actual money and services paid to unhinge the injustices that perpetuate various kinds of slavery depends on the context in which we discuss freedom. But there is always a cost of some format, and grace is like that. Grace comes at cost, not in a substitutionary atonement kind of way where a vindictive god had to kill his son because we’re all evil but in a kind of way that acknowledges we killed a Man because He rocked our world too far and God took that death and made it redemptive, made it holy, makes us holy a little piece at a time when we realize that God extends grace and then asks for everything that we have ever been and ever will be in return. I bring up my plants, which my mother has adopted in the recognition that she’ll never get human grandchildren from me, because a while back Ralph and Gwen got flowers and I freaked out. I called Discretion to essentially have her explain to me what was happening (no, not in a “birds and bees” kind of way, but in a “do I need to re-pot them or give them different kinds of sunlight or whatever” way). After laughing at me for a solid 15 seconds, she said this is how plants work and no, I didn’t have to do anything differently. They would be fine doing their merry little thing, and if the extra shoots became too difficult to sustain I could break them off or they would fall off as the plant cared for itself. In fact, Discretion told me, I would do more harm than good if I tried to micromanage these new growths—or if I tried to stunt them altogether, refusing to let my plants “grow up,” in a way.

I bring up my plants, which my mother has adopted in the recognition that she’ll never get human grandchildren from me, because a while back Ralph and Gwen got flowers and I freaked out. I called Discretion to essentially have her explain to me what was happening (no, not in a “birds and bees” kind of way, but in a “do I need to re-pot them or give them different kinds of sunlight or whatever” way). After laughing at me for a solid 15 seconds, she said this is how plants work and no, I didn’t have to do anything differently. They would be fine doing their merry little thing, and if the extra shoots became too difficult to sustain I could break them off or they would fall off as the plant cared for itself. In fact, Discretion told me, I would do more harm than good if I tried to micromanage these new growths—or if I tried to stunt them altogether, refusing to let my plants “grow up,” in a way. But anyway, a friend of mine loaned me his copy of George MacDonald’s

But anyway, a friend of mine loaned me his copy of George MacDonald’s